Despite my mid-night web browsing, I still awoke well before my alarm went off, and had plenty of time to take in the scenery before breakfast:

|

| Sunrise over Soda Lake |

|

| Early morning at Soda Lake |

|

| Male phainopepla--one of many species that I saw for the first time during this trip |

I was impressed to see that many of the students were also up and about; a dozen or so climbed up the hill behind the DSC in order to see the sunrise from on high. I don't think any of the students packed binoculars, which is a real shame; there were many interesting things to be seen in the Mojave and, later on, in the redwood forest. The most common species at the DSC was, by far, the house finch; hundreds of the chatty birds could easily be seen flying around the oasis in big, noisy groups. There were also some smaller flocks of cedar waxwings and lesser goldfinches, the latter of which was another new species for me. I saw a number of black phoebes, dozens of ravens (some flying around displaying nesting material in an obvious bid to gain a breeding partner), and--to my tremendous excitement--greater roadrunners.

|

| Greater roadrunner with a dead lizard in its bill. I first located the bird by ear; having a full mouth didn't stop this male from singing repeatedly from his hilltop perch. |

Of course, there were many other interesting species, as well--not just birds, but also plants, reptiles, and insects. Some of these could be found right outside our doors:

|

| Unknown beetle species found just outside my room at the DSC |

Although I could easily have spent the day wandering around looking at wildlife, I had been given a very different itinerary: Caitlin and I were taking our group of human geographers to Calico Ghost Town, about an hour away from the DSC and not far outside Barstow. Calico is a very odd place, which is exactly why we took the students there. It is an uneasy mixture of history, culture, and, above all else, commercialism. One can learn about the town's past there, but only through a good deal of effort; by both chance and choice, its primary purpose is to cater to tourists who stop there for lunch while driving between Los Angeles and Las Vegas.

|

| Calico Ghost Town, as seen from the outlook point at the far side of town |

Within about five minutes of entering the town, I was convinced that I was going to have an incredibly difficult time spending 7 hours there. To my surprise, however, I ended up quite enjoying myself. As a group, we spoke with the town's manager, an incredibly friendly and plain-speaking woman who welcomed both our questions and our feedback; she gave us a fascinating behind-the-scenes look at what it is like to run an attraction/preserve/historical monument on a small budget, all while generating enough funding to support not only that site, but also several others in the county. Talk about pressure.

All of us also did quite a bit of people watching--something that became much easier from about 11 AM onwards, as busloads of tourists began to pull up and descend upon the town to eat burgers, drink milkshakes, snap photos, and maybe pick up a few souvenirs. The vast majority of tourists were Asian; according to the manager, Koreans are particularly common there. Many of them spoke little or no English, which made me wonder whether they actually thought they were getting a genuine "Old West" experience (they weren't).

|

| In their reports on Calico, several of the students referred to it as "cheesy." Indeed, much of the "culture" there was very calculated and inauthentic. |

|

| Calico schoolhouse in front of some of the area's remarkable geology |

Only a couple of Calico's buildings are original; the rest are replicas built sometime since the park opened in the first half of the 20th century. I'm not sure how well the other replicas mimic their original counterparts, but the schoolhouse is amazing--there is a plaque showing a 19th-century photo of the first schoolhouse, and you really cannot tell that it is not the same building that is there today. I thought it was a shame that you couldn't go in and look around; all you can do is peer through the dirty glass of the front door.

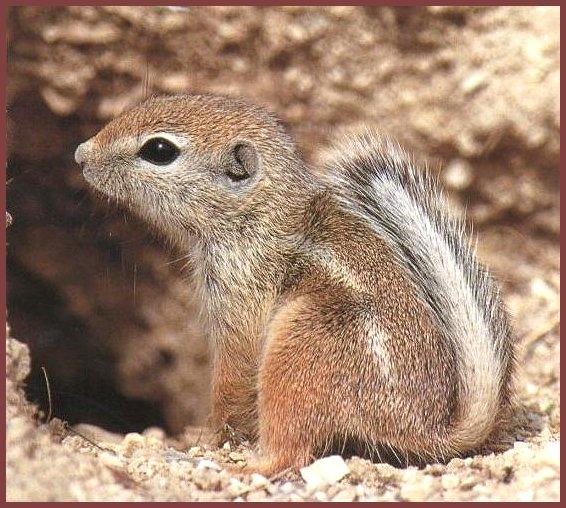

Probably my favorite activity was climbing up to the lookout point and sitting in the sun while the desert breezes whooshed across the hilltop. Although the point is only slightly removed from the rest of the town, I couldn't hear any of the activity down below me; the only sound was the wind. I was hoping that the perch would be a good spot to do some birdwatching, but I failed to see or hear any avian wildlife. However, I did spot a Nelson's antelope ground squirrel--one of the few mammals that I observed during our adventure.

|

| I was not close enough to the squirrel to get a good photo--this one is courtesy of memozee.com. |

|

| The Calico train, exploring old mines where silver and borax were once unearthed by people who worked 12-hour shifts underground |

The overlook also provided a good view of the Calico Train, which offered short tours of the mines and their environs. I probably should have taken a ride on the train, but, like everything in Calico, it was very expensive and gave little information in exchange for the fare. So, I just looked at it from afar.

Eventually, the crowds began to thin and the students wrapped up their one-day research projects, so we headed back to the DSC. We didn't have any activities planned for the evening, so we were able to take in the sunset, enjoy another filling dinner, and then turn in early (hoping in vain for an end to the jet lag).

|

| Alkaline lakes are the perfect habitat for flamingos--of both the feathered and plastic variety. These two are basking in another lovely desert sunset. |

The next day, Caitlin and I hit the road again in order to take our human geographers back to Barstow to visit the Mojave River Valley Museum. Because she hadn't heard back from the museum staff for several weeks, Caitlin wasn't sure what we would find when we showed up; she half expected that the museum might be closed. Instead, we arrived to a friendly welcome and a magnificent spread of food--fruits, veggies, dips, chips, bagels, spreads, English muffins (just for a laugh), and hot beverages. The museum staff had invited several local experts to come speak to us and usher us around both the museum and several other sites in the Barstow vicinity. Also at the museum was a reporter from the local newspaper; his story about our visit made the front page of the Daily Press the following day.

After we had finished looking around the museum's indoor and outdoor displays, our hosts escorted us to the Desert Discovery Center (DDC) a couple streets away. The DDC is primarily an educational facility, as well as the home of the Old Woman Meteorite--the second largest cosmic rock in the country. However, the most interesting thing at the DDC was not from outer space--though it was so weird that it might as well have been. I'm referring to our host there, an employee of the Bureau of Land Management. To my knowledge, I have never spoken to anyone under the influence of cocaine, but I imagine that such a person would act like this guy; he was a hyperactive fast-talker with a love of conspiracy theories and an inability to self-censor. He divulged that he had been on a "spiritual journey" for the past several years, and that this journey had involved "alchemy." I don't know what, exactly, that means, but I'm thinking that he probably does lots of drugs (simultaneously).

|

| A fuzzy cell phone photo of the Old Woman Meteorite in Barstow |

|

| Not much going on out here |

Daggett is no booming metropolis these days, but it used to be more exciting back when there was more mining activity in the region, and when there was more money to be made from railroads. We didn't really go there to see Daggett itself, but to meet with Bob, the president/director of the Mojave River Valley Museum. Bob, who is a professional blacksmith (yes, they still exist), generously spent his entire lunch break chatting with us; he wanted to show us some old wagons and tell us a little bit about how the blacksmiths of yesteryear used to fashion wheels and other metal bits and pieces.

|

| Old wagons in Daggett |

Bob was another real character--someone who looked like he had walked off a movie screen. As we chatted to him, we were standing outside, in a desert, under the midday sun, and yet he was wearing a woolly hat (with ear flaps), jeans, some sort of insulating undershirt, and a quilted flannel jacket. I was hot just looking at him. He was a wiry guy made lean and tough by years of smithing and, to judge from his comments about hiking, exploring the nearby desert. He was also incredibly knowledgeable about history, and I wish we'd been able to visit when he had more time to devote to answering questions and telling tales about his adventures in the Mojave.

Our final destination was the Marine Corps Logistics Base--or, to be more precise, a pile of rocks at its entrance. Many of the rocks were decorated with petroglyphs of unknown age; some were definitely hundreds of years old, others may have been thousands of years old. Those, of course, were made by the region's original inhabitants, though there were also some markings added by settlers later on.

|

| Petroglyphs on rocks outside the Marine Corps Logistics Base just outside Barstow |

I was thrilled to have an opportunity to see the petroglyphs, and impressed that the folks at the base had thoughtfully fenced in the rock pile to protect it from vandals and developers. It's amazing to think that the Mojave Desert is full of artifacts like this--petroglyphs, old spearheads, mortar stones, even plants that still bear evidence of historical management by Native Americans; they're all just waiting to be discovered by people with the fortitude to venture out into the unwelcoming land and do a bit of searching.

It would have been great to spend the rest of the afternoon learning from Barstow's local historians, but we had to get back to the DSC in order to make the van available for a post-lunch physical geography day trip. Although I was predominantly working with the human geographers during our time in California, I had been asked to act as chauffeur to the other students on this occasion because I was one of only two people with an American driving license. I was more than happy to oblige because it gave me an opportunity to see more of the desert and to learn about something I had pretty much no experience with whatsoever: volcanoes.

|

| A view down Kelbaker Road, which runs through Mojave National Preserve. The dark stuff on the left is a hardened lava flow. |

My colleague Kate is an expert in volcanoes, so she organized this side trip in order to give the physical geographers something more exciting to see than an alluvial fan (which is what they had been visiting for the first day and a half). The trip involved three main attractions: one of many lava flows by the side of the road, a lava tube at the end of a dusty dirt track, and the many cinder cones spread out between the first two destinations.

|

| Panoramic shot of cinder cones in the Mojave Desert |

As you might expect given that the area contains lava flows, lava tubes, and cinder cones (a variety of volcano that spews dust and rock), the Mojave Desert was once pretty geologically active. These days everything is dormant, but the evidence of past events is not hard to find. Many plants have colonized the lava flows, but it is still easy to see the dark volcanic basalt underneath all the cacti and wildflowers. The flows cover such incredible stretches of land that it is hard to imagine what the area must have looked like when the lava was still hot, spreading out across the landscape and consuming everything in its wake.

|

| Barrel cactus nestled among the hardened lava |

Because there was a shortage of hard hats, I never did go into the lava tube, though I did stand in the entryway and inspect some of the hardened lava up close. I was more interested in wandering around looking at desert flora and straining to hear any signs of bird life; I was much more successful at the first goal than the second.

|

| Beavertail cactus in bloom atop a lava flow |

Although we tend to think of deserts as barren, miserable places, they can actually be full of life; this was certainly true of the Mojave. Rather than finding the desert bleak and depressing, I found it to be surprisingly peaceful and calming. I'm not saying that I'd want to be there at midday in the middle of the summer, but late afternoon in springtime is certainly quite lovely.

We returned to the DSC after making a quick stop for medicine in Baker; one of the students had developed a severe cold that eventually infected two of my colleagues and, predictably, me. It seems I am not allowed to take a trip to America unless it involves some sort of illness. The cold, however, was not to materialize for a few days; before I got to that I had to weather a migraine that appeared the following morning. I was supposed to go to the lava tube again with the second of three groups of students, but instead I had to hand that duty off to Caitlin and hope that my headache medication would bring quick relief.

Indeed, terrible as I felt at breakfast, I was back on my feet within an hour or two. I took advantage of my remaining free time by exploring the grounds around the DSC. As per usual, I went looking for birds and flowers, but I also checked out the facilities--both the modern ones and the remnants of previous structures. I've always been drawn to ruins, and the ones at Zzyzx are very photogenic.

|

| I love all the old signs at Zzyzx--the font is very "Wild West," though the signs are only about 50 years old. |

|

| The interior of the old pool house, plus bonus sunrise in the background. |

Perhaps the most photogenic area was the "car graveyard," which contained vehicles that had died anywhere from 40-80 years ago. I had been reminded of the movie Cars while driving along the main street in Barstow, and those thoughts returned to me while I wandered around the graveyard; with their headlights and grills, many of the retired cars appeared to have sad little faces looking back at me.

|

| Sad-faced car |

|

| Power lines stretch into the desert |

After lunch, I headed out for the last of the three volcano trips. During this one, Kate decided to take the students up to the top of a cinder cone so they could look down into the crater. As a result of the elevation, we got an even better view of the desert and the remnants of the geological upheaval that had occurred there tens of thousands of years ago.

The rest of the trip was basically like the one the day before, except that a couple of the students had a mishap with a cactus during our visit to the lava flow. One of them grabbed a hunk of beavertail cactus because he "wanted to see what it felt like." While the first student was swearing and clutching his hand in pain, a second student decided to pick up the same chunk of cactus and nibble at it in order to investigate its flavor. Needless to say, he also wound up studded with cactus thorns. I could not muster much sympathy for either of them and, frankly, was more concerned about the poor cactus that they'd injured.

Most of the evening was spent packing and preparing to depart Zzyzx the following morning. Shortly after dinner, though, Caitlin and I met with the human geographers in order to hear about what they had learned about the area; they had spent the past day and a half reading books, interviewing locals, and exploring the habitat while investigating the cultural significance of the oasis. They did an excellent job synthesizing information on ecology, hydrology, geology, culture, and history--no mean feat considering how disparate those fields are often thought to be.

I don't think any of us stayed awake for too long after the presentations, since the next morning was scheduled to be an early one, followed by a long and tiring day in the bus. Although I didn't waste too much time heading off to bed, I did pause long enough to make one last friend in the desert:

No comments:

Post a Comment